Sign up for our newsletter, to get updates regarding the Call for Paper, Papers & Research.

Child Labor: The Human Trafficking Exploitation in Nigeria.

- Ihuoma Ogechi Anurioha

- 2283-2293

- Mar 24, 2024

- Artificial intelligence

Child Labor: The Human Trafficking Exploitation in Nigeria.

Ihuoma Ogechi Anurioha

Florida Atlantic University

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.47772/IJRISS.2024.802163

Received: 30 January 2024; Revised: 13 February 2024; Accepted: 20 February 2024; Published: 24 March 2024

ABSTRACT

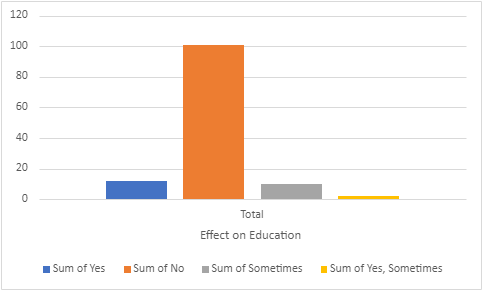

This paper examines the issue of child labor and human trafficking exploitation in Nigeria. These practices deprive children of educational opportunities and normal childhood development, propagating cycles of poverty. Various cultural, socioeconomic, and religious drivers enable the persistence of child labor despite legislative interventions. This study utilizes mixed-methods data involving qualitative and quantitative approaches to explore the nature, contributors, and impacts of child labor in Nigeria by reviewing scholarly journals, reports, statistical data, and policy documents. Factors analyzed include cultural attitudes, poverty, porous borders, gender norms, and the breakdown of Islamic educational apprenticeships. Consequences across health, psychology, education, and national growth are scrutinized. Governmental efforts and remaining gaps are assessed. Results revealed that cultural acceptance of child economic roles, especially for girls, and endemic poverty drive families to perpetuate child labor traditions. Economic integration policies enable trafficking across West African borders. Nigeria’s Almajiri Qur’anic education system has deteriorated, with many boys now begging or working for survival rather than studying. The result is vulnerability to further exploitation. A novel finding from this study revealed that about 80.5% of participants responded that their child labor experiences did not affect their education, contrasting existing research that found child labor to limit schooling in Nigeria. Few victims develop lifelong health issues and trauma. In some cases, erratic education also propagates intergenerational poverty. Although Nigeria has implemented institutional interventions, enforcement gaps allow child labor to persist. Extended research into policy efficacy and poverty reduction initiatives are warranted to alleviate cultural and economic strains compelling child labor to neglect human rights.

Various forms of child labor exist in Nigeria that bother down on child abuse. Millions of children are deprived of childhood innocence because of these traumatic experiences. There is the general assumption that in every African society, the extended family system provides care, love, and protection to all children, but this has invariably escalated the prevalence of child labor within that region. Children are forced to do jobs that can be termed child labor in the guise of family duties. This practice is attributed mainly to the culture and tradition of the rural society (Okeahialam, 1984). Cultural influence on child raising helps explain the country’s high prevalence of child labor. According to Fetuga et al. (2025), the Ijebu Yoruba people of the Southwestern part of Nigeria are noted for their hard work. They expose their children to family economic operations at a young age. This study examines the nature of child labor in Nigerian society. It will also explore some policies and regulations set up to curb its prevalence and the extent of its effects.

Over the decades, there has been a radical shift away from the binary into the non-binary of the understanding surrounding the phenomenon of human trafficking. The media play a significant role in influencing public views of crime and developing legal responses to it. The media has long overemphasized sexual exploitation while downplaying other forms of human trafficking, such as child marriage, labor exploitation, and organ trafficking (Rodríguez-López, 2018). Historically, during the era of the slave trade, people were sold and trafficked as commodities to benefit the slave traders. Despite the eradication of the slave trade, human trafficking has continued to take on specific shapes and forms over the decades. Forced labor replaced slavery, and human trafficking replaced the slave trade, now known as modern-day slavery (Kara, 2011). Next to the sale of illegally obtained weapons and drugs, human trafficking has been rated to be the fastest-growing and third most lucrative organized crime globally (Miko, 2004). Even though anti-trafficking efforts have been adopted globally to curb human trafficking, many nations still struggle to find a lasting solution to end its prevalence. The menace of child labor has been rampant worldwide in human history. Globally, every five minutes, a child dies from maltreatment (Ahad et al., 2021).

Minors under 18 years are considered children, as contained in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, 1989). The Convention strongly emphasizes the necessity of safeguarding children from abuse, exploitation, and violence, as well as from dangerous jobs and workplace conditions.

Nigeria ratified the Convention in 1991 and enacted the Child Rights Act of 2003, clearly defining everyone under 18 as a child. Child labor is any work that hinders a child from his or her childhood and the right to an education or harms the child’s physical, mental, moral, and social well-being. As a result, work is considered child labor if it is exploitative or harmful to any component of the child’s developing personality (Nwazuoke & Igwe, 2016). This paper explores the practice of child labor in the West African country of Nigeria, which is multi-ethnic and has diverse cultures that shape their way of life and beliefs. Political and economic instability has caused a rise in the country’s poverty level, increasing the exploitation of children through culturally accepted forced labor.

This study utilizes mixed-methods data, which combines a qualitative and quantitative approach. Here, the study employed thematic topics from a quantitative research approach to produce data from participants’ lived experiences to analyze how child labor operates through cultural notions and behaviors. The study focused on the practice of child labor in Nigeria. The impact of laws and regulations in preventing this crime was also considered in the study. One hundred and twenty-five (125) people responded to a survey, and participants were reached from diverse ethnic groups in Nigeria. Those who had been involved in any child labor during their childhood were eligible to participate in the poll. Participants had the option not to participate and were informed that the data they provided would be kept entirely anonymous to preserve their privacy. Therefore, no identifying information was placed on the survey sheet. This study also used secondary sources, including papers, scholarly publications, statistical data, and policy documents.

According to the Trafficking in Persons Report (2022), published by the United States of America Department of State, Nigeria has a high level of trafficked persons. It has been placed on tier 2, which means the country does not fully comply with the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, 2000 (TVPA) minimum standards, but it is making significant efforts to comply with these standards. The country made an effort to investigate more traffickers, including two Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) members accused of sex trafficking; to investigate officials accused of being complicit in trafficking crimes; to identify and provide more services to victims; and to develop and implement an expedited form of identifying victims of human trafficking. The government, however, faulted in meeting the minimum required standards in several crucial areas like failure to prosecute any member of the CJTF for prior child soldier recruitment or use, potential sex trafficking in government-run internally displaced persons (IDP) camps, which pose a serious concern, and officials removed fewer children from conditions of forced labor.

The absence of schools in several communities, leading to education apathy and a large scale of poverty in Africa, has aided the exploitation of children who take up jobs as maids in homes and are popularly called “house-help.” These children are taken as housekeepers so their parents or guardians might profit from their labor. Fetuga et al. (2005) observed that declining parental education and socioeconomic class contributed to the prevalence of child labor in Nigeria. The necessity for a developing child to focus on activities that can help them realize their full capabilities and the need to steer clear of potentially “harmful” activities are concepts that properly educated parents are more inclined to comprehend. Additionally, parents are less under pressure to send their kids to work when they have a higher socioeconomic status.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) liberalization and free trade policies make the easy cross-border movement of people and goods possible. Under the guise of work possibilities, traffickers entice unsuspecting victims across the border by taking advantage of the lax laws in ECOWAS member countries (Raimi, 2012). When the victims arrive in Nigeria, they are made to work as domestic workers, servers in beer bars, and sometimes even dangerous occupations in illegal mines. The prevalence of “Kabre children,” primarily boys in their mid-teens from Togo who are trafficked into Nigeria to work on farms in return for room and board and a year-end prized motorcycle, is increasing. Their girls are also trafficked to work as domestic laborers or in the sex trade (Piot, 2011). Parents blamed this growing practice on poverty, which aided the trafficking of their children and enriched the pockets of intermediaries and wealthy Nigerian landowners. These children return to their country worse off than when they left. Some boy returnees complain of fatigue and cannot do farm work after being drugged with stimulants to enable them to work twice the labor they usually do for their age. The result is an adverse effect on their health. The girls sometimes return with HIV/AIDS infections.

When asked if they were adversely affected as a result of the work they did as children, some of the participants reported several traumatic events they encountered:

Yes, it affected my academics schedule, I used the time for school to farm and help my parent in selling goods in the market, instead of reading (male respondent, 16 years below involved in farming and street vending).

Yes, it caused a poor academic performance for me (male respondent, 10 years below, involved in street vending)

It was beyond my physical capacity as I had to lift heavy loads most times. This gave me lots of pains after work and I wasn’t happy I was doing the job (male respondent, 17 years and above)

Yes. I was almost kidnapped while being alone in my mum’s shop (male respondent, 10 years and below, involved in household chores, street hawking, and errands ).

Not really, because my siblings and I were doing the chores with joy (female respondent, 16 years below, involved in “household chores and subsistence farming with my parents back then in the ’90s”).

I was not allowed to go to school, I had to enroll myself in school (female respondent, 17 years and above)

Somehow no, because I thought it was how life was, after the loss of my mother to death (male respondent, 10 years below).

It deprived me of sleep/rest most time (Female respondent, 16 years below).

It hurt my back so bad (female respondent, 10 years below involved in farming)

Sure. many times I work barefoot to work and school. Many times am beating till there is a hole in my head and am left to bleed. No medical attention was given to me (male respondent below 10 years involved in “household chores, street vending, babysitting/nanny”).

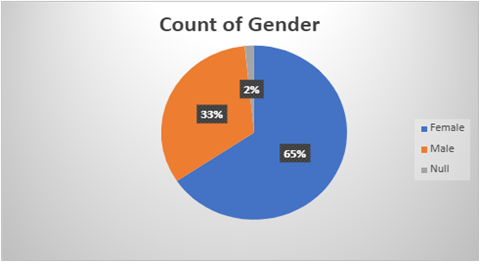

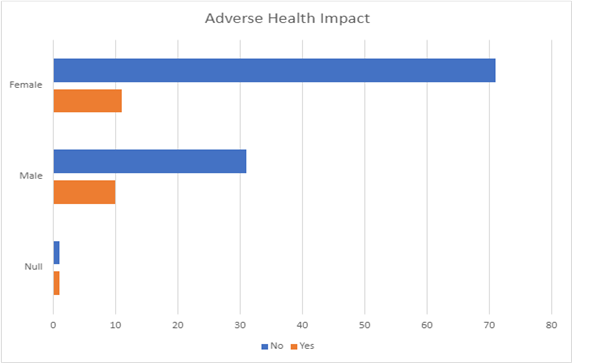

Gender inequality also plays a crucial role in the prevalence of child labor in Nigeria. Among children who worked, girls outnumbered boys by a wide margin. In line with prior findings, gender bias in upbringing targeted training girls for traditional responsibilities of small-scale commercial trades to increase family income (Fetuga et al., 2005). Girls in traditional African societies are more versatile and responsive to parental authority and are more frequently allocated economic responsibilities. In some states of the country, mainly the Northern states, girl children are usually prevented from acquiring higher education and are relegated to caring for the home till they are married off, even at a very young age. The boys go to school to acquire an education, as they are required by society to grow up, marry wives, and become the providers and breadwinners of the home. The girl children are commonly seen fetching water with big buckets from the stream, grinding maize on a stone, and doing other household chores to make the home comfortable for their parents and siblings. The survey statistic reveals a demography of 66.9% Female and 33.1% Male.

Religion cannot be downplayed in its contributory role to the prevalence of child labor in the country. Due to pervasive poverty in northern Nigeria, many families are compelled to send their children into vulnerable Almajiri apprenticeships. According to Onuoha (2012), families in this system send their young boys to live with a Malam or Islamic instructor so they can study the Qur’an and other Islamic texts. However, due to many Malams having financial difficulties, many Almajiri children are forced to work as menial laborers or as street beggars to pay their teachers and survive, depriving them of opportunities for education and personal development (Muhammad et al., 2020). These children may go without adequate food or shelter. Although evidence remains limited, information indicates that some almajiri in Nigeria may undergo deliberate scarring or injuries to arouse sympathy and thus encourage donations (Magashi, 2015). The region’s high rates of child labor, poverty, and trafficking victims have been strongly correlated with the Almajiri system’s deterioration (Ahmad and Alkhali, 2022). Traffickers frequently target young people in Almajiri for exploitation because of their extreme poverty and lack of supervision (Odumosu et al., 2013). The existing system’s educational and financial underpinnings must be drastically changed to lessen related breaches of children’s rights. Almajiri enrolment is rising despite the economic downturn, and research suggests that this system disproportionately promotes juvenile labor and human trafficking, necessitating legislative intervention.

The loss of parents or the divorce of spouses often traumatizes children left at the mercy of their stepfathers, stepmothers, or other relatives who exploit their vulnerability for selfish profits through child labor (Igwe & Nwazuoke, 2016). They are sent to live with their parent’s relatives, where they are made to do all the work beyond their age. These children do all the home chores and are later forced to wander the streets hawking and trading different wares for their guardian’s profit. There is always the tendency to become street kids who end up as juveniles.

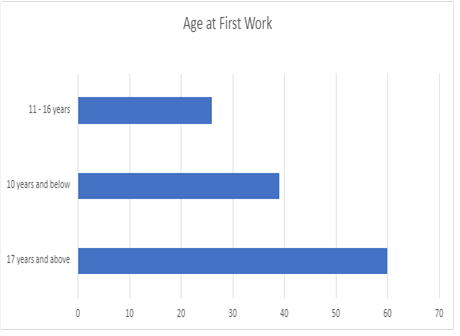

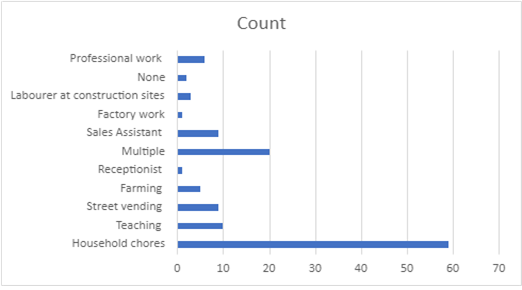

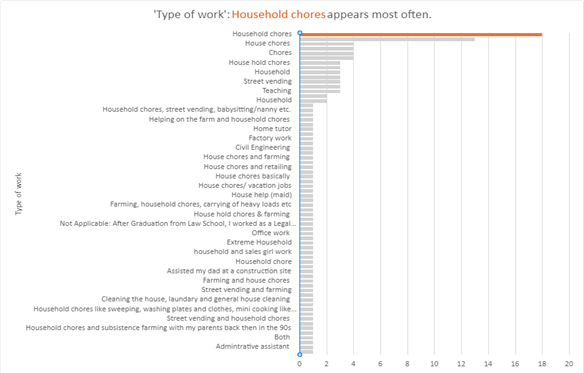

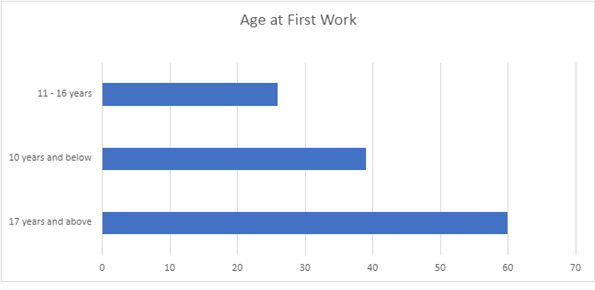

According to Agunwa et al. (2021), children used for child labor are prone to miss school and fare less well academically than their peers. The above statistic reveals an 80.5% – No impact on education. This contrasts generalized typical findings that child labor limits schooling, signaling possible normalization. It further changes the stereotypical notions that child labor is very harmful to children’s education in Nigeria, frequently leading to students dropping out or staying in school longer. Most kids who engaged in labor-related activities did so under one or both of their parents’ guidance to support the household budget, and also went to school. Children of low socioeconomic positions or parents with less education were heavily involved in labor activities. Additionally, there was a strong correlation between child labor and an increased number of children in a family (Fetuga et al., 2005). However, it is essential to emphasize that not all forms of labor are deemed child labor. For low and middle-income countries like Nigeria, it is typical for children to work together with their parents or other adults on light chores at home that are not harmful to children’s social and psychological development, as is still practiced in many African countries today. Data collected revealed that over half (54%) of the participants started working under 17, with 32% beginning at 10 or younger. This confirms that child labor is a common experience and very much prevalent in the country.

Participants identify poverty, family financial support, parental neglect, and cultural norms as primary drivers for the perpetuation of child labor in the country through their responses:

- Parental neglect, lack of sponsor, poverty (respondent who started work below 10 years)

- Poverty Ineffective government policies on child labor (respondent who started work below 16 years)

- Early death of parents, also poverty and generally lack of infrastructures. (respondent who started work of farming, household chores, and carrying of heavy loads below 10 years)

- Financial purposes. To help their parents (respondent who started work in street vending below 16 years)

- Poverty Ineffective government policies on child labor (respondent who started the work of teaching below 16 years

- Help their family (respondent who started house chores below 10 years)

- Lack of parenthood. Parent negligence. Death of parents (respondent who started the work of street vending and house chores below 10 years)

- It’s always been a norm in the Nigerian culture. It’s a sign of respect towards your parents or family at large (respondent who did extreme house chores below 16 years. She stated that it deprived her of sleep sometimes)

- I was doing household chores. It was because we didn’t have house help so as the first child and a girl I have to help my mum in caring for younger ones and doing house chores. But so many parents sent their children to do this type of work because of poverty. A lot of families can’t afford basic needs of the family, so they sent the children out as means to get to there needs. (respondent who started work below 10 years)

- House chores are part of moral upbringing when a child does it happily and is rewarded afterwards or appreciated (respondent who started house chores 17 years below).

- Culture, poverty, death, absence of governance & extended family relationship and mentorship (respondent who started doing house chores and selling to support her family below 10 years ).

- It’s part of the child’s upbringing and training they receive as African children (respondent who did house chores below 10 years)

- Children with poor background are easily abused and no one will say a thing or even care. Many times the parent of the child gave the child away to be used as child slave worker. In my case it was my parent that gave me away for 10yrs (respondent who did household chores, street vending, and babysitting/nanny below 10 years).

There are significant psychological, physical, and social consequences that affect young people involved in child labor, which spread across the community. An in-depth examination of these intricate effects highlights how much more critical reform and preventative measures are. Some individual health problems throughout life may be associated with hazardous child labor. According to the survey, about 20% of Nigerian children face health issues in both rural and urban areas, revealing that child labor can be harmful to children’s health and physical development. Simkhada et al. (2018) report that among young people who were trafficked at a young age, there is a higher prevalence of STDs, unsafe abortions, pelvic inflammatory disease, and unwanted pregnancies. Psychological trauma can also lead to higher rates of suicidal thoughts, violence, sadness, anxiety, PTSD, and attachment disorders (Ottisova et al., 2018). Extended work hours impede children’s growth and prevent some from participating in formal education. Lack of access to education limits future socioeconomic opportunities and perpetuates the poverty cycle across generations (Adeleke and Alabede, 2022).

Child labor and trafficking have a financial impact on the economy in the form of lost human capital, decreased productivity, increased healthcare costs, a weakened legal system, and slower GDP growth (Pereznieto et al., 2014). As a result, the consequences range from a single child to structural concerns inhibiting the progress of the entire country.

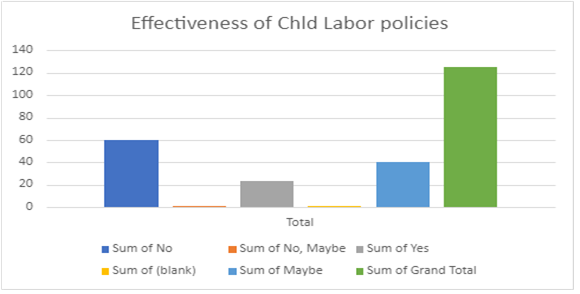

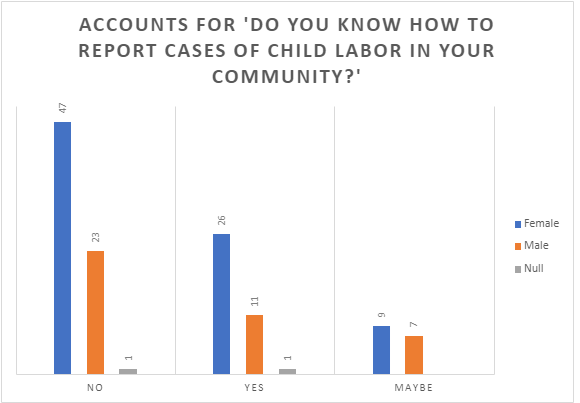

Given the seriousness of the repercussions of child labor, international organizations and the Federal Government of Nigeria have devised strategies to combat child labor in the country. The United Nations Children’s Education Fund (UNICEF), The International Labour Organization (ILO), and other Non-profit Organizations (NGOs) have all proposed solutions to the problem. By establishing the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP) in 2003, which was created by the Trafficking in Persons (Prohibition) Enforcement and Administration Act 2003, the Nigerian government is responsive in the battle against human trafficking. The NAPTIP has continued its monitoring over the Nigerian border, arrests of suspects, questioning of suspected traffickers and rescue of victims, provision of refuge and security for survivors of trafficking, and rehabilitation as part of its responsibilities and with significant funding. In addition to prosecution, there is effective sensitization and education to foster ongoing awareness of human trafficking (Raimi, 2012). However, despite the efforts of these organizations, child labor practices persist in the country. Participants were asked about their perception, from their lived experiences, of how effective these child labor policies were in combating its prevalence. 62% knew laws, but only 19% thought them effective. Furthermore, only about 29% knew how to report local child labor cases.

This study found that, despite attempts to safeguard children, the children in Nigeria remain vulnerable to child labor. The failure of child protection measures stems from several variables that continue exacerbating child vulnerabilities. Child labor was outlined as any work harmful to a child’s physical, mental, moral, and social well-being. This study investigated the exploitation of children into forced labor, which has been on the increase globally, and how this phenomenon has become a practice culturally assimilated into the homes of the Nigerian citizenry. Lack of education, poverty, religion, loss of parents, gender inequality, and porous cross-border movement have been linked as contributory factors that aid child labor in the country. The effect of child labor can lead to the proliferation of at-risk juveniles. A novel finding from this study revealed that about 80.5% of participants responded that their child labor experiences did not affect their education, contrasting existing research that child labor limits schooling, which signals possible normalization. Despite the establishment and provisions of several International and National agencies, child labor continues to persist. The main drivers identified were poverty, family financial support, parental neglect, and cultural norms. This aligns with the literature on the socioeconomic roots of child labor in Nigeria. Overall, the results highlight the ubiquity of early working ages due to financial stresses. The minimal perceived impact seen as “norm” signals the extensive cultural acceptance driving child labor’s persistence despite legislation attempts. Boosting enforcement while elevating economic conditions for families appears critical to shifting cultural attitudes and preventing exploitation.

This study has certain limitations inherent to literature evaluations on complicated socioeconomic topics. First, the observational analysis has limitations in terms of determining causality. Conclusions on the relationship between certain cultural and socioeconomic elements and child labor rates are correlational rather than proven causality. Controlled, empirical studies that study communities across time might provide more accurate causal linkages. Secondly, determining the generalizability of outcomes is difficult because most studies focus on specific locations or subcultures. For instance, the attitudes of predominantly Christian southern tribes about child labor may differ from those of predominantly Muslim Hausa tribes in the north. To improve generalizability, more geographical, cultural, and religious diversity throughout Nigeria should be investigated in future studies. Although this qualitative study drew conclusions from reliable sources and outlined essential trends on the causes and effects of child work, quantitative, moral primary research could further strengthen the inclusion of children’s voices, causal confirmation, and representations. Policy improvements can become more evidence-based and responsive to stopping child exploitation as academics build upon these constraints.

The Nigerian government has taken significant steps in policies to tackle this crime. However, there is a need for the strict implementation of these policies and regulations to end this scourge. Parents and guardians found guilty of engaging in and procuring child labor or giving their children out to traffickers for child labor should be prosecuted. More study is required to evaluate the success of Nigeria’s National Policy on Child Labor and determine the long-term effects of the policies and initiatives put in place to address child labor in the country. This could be expanded upon in future studies by examining data over an extended period to see if declines in child labor have persisted for decades. Longitudinal research on the educational, health, and economic paths of kids taken out of child labor would also shed light on the treatments’ long-term effectiveness. Fetuga et al. (2005) investigated the frequency of child labor in Nigeria; however, additional information is required regarding different types of human trafficking exploitation and the pathways through which Nigerian children are labor-trafficked, both domestically and internationally. In order to educate policy, research should also examine the connections between different types of trafficking, such as forced labor in industries, sex trafficking, and domestic slavery.

Cross-national cooperation will be significant in reducing human trafficking networks that span several African countries. Subsequent investigations ought to assess current collaborations among Nigerian organizations and foreign nations, pinpointing optimal methodologies and opportunities for enhancement in cooperative anti-trafficking campaigns. This would be essential to quantify the results achieved by the prosecution and victim support programs. Novel technical and community-based approaches hold great promise for stopping human trafficking and helping Nigeria’s most vulnerable children. However, the survey results revealed that only about 29% of individuals knew how to report local child labor cases, signaling the need for more awareness of the monitoring and enforcement avenues required.

Trialing and thoroughly assessing such innovations as SMS-based applications that link kids to social services or neighborhood watchdog initiatives needs further research. Successful pilots’ cost-effectiveness and scalability ought to be explored. Children of school age should not be seen wandering the streets hawking, especially during school hours. The Government of Nigeria should enforce the pertinent local and international laws against child labor. Several existing policies are currently in place, but lack of implementation has seen the continued practice of child labor in the country. More assessment is needed on definitions of hazard risks to children. There is also the need to reform the almajiri system and return it to its original design of inculcating knowledge rather than a means of livelihood through begging. The Nigerian government should put more effort into eliminating poverty and raising living standards in all areas of its economy. Poverty has been proven to be a powerful tool that encourages the spread of child labor in the country. Smaller family sizes, parental education, and family economic advancement would relieve parental pressure to involve their children in labor activities.

REFERENCES

- Adeleke, R., & Alabede, O. (2022). Geographical determinants and hotspots of out-of-school children in Nigeria. Open Education Studies, 4(1), 345-355. https://doi.org/10.1515/edu- 2022-0176

- Adesina, O., S. (2014). Modern-day slavery: poverty and child trafficking in Nigeria. African Identities, 12(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2014.881278

- Agunwa, C., C., Enebe, J., T., Enebe, N., O., Ezeoke, U. E., Idoko, C., A., Mbachu, C., O., & Ossai, E., N. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of child labor among junior public secondary school students in Enugu, Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 21, 1339. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11429-w

- Ahmad, M. A., & Alkali, M. B. (2022). The Crisis of National Security: Implications of Almajiri in Northern Nigeria. Port Harcourt Journal Of History & Diplomatic Studies 9 (1), www.phjhds.com

- Fetuga, B.M., Njokama, F.O., and Olowu, A.O. (2005). Prevalence, types and demographic features of child labor among school children in Nigeria. BMC Int Health Hum Rights, 5(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-5-2

- Kara, S. (2011). Supply and demand: Human trafficking in the global economy. Harvard International Review, 33(2),66–71. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A261641041/AONE?u=gale15691&sid=googleSchola r&xid=ff11c0e3

- Magashi, S. B. (2015). Education and the Right to Development of the Child in Northern Nigeria: A Proposal for Reforming the Almajiri Institution. Africa Today, 61(3), 65– 83. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.61.3.65

- Miko, F. T. (2004). Trafficking in women and children: the U.S. and international response. CRS Report to Congress. Washington, DC: The Library of Congress. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20010801 RL30545 18350f9e73685f641b54b4f929553d7088849d9.pdf

- Muhammad, A. K., U. A. Beatrice., & A. A. Gwandu. (2020). Scaling-down Domestic Violence against Children in Nigeria for Sustainable National Development. International Journal of Educational Benchmark (IJEB),15 (1) eISSN: 2489-0170 pISSN:2489-4162

- National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons and Other Related Matters (2015). Data on Human Trafficking in Nigeria. Retrieved from https://www.naptip.gov.ng

- Nwazuoke, A., N., and Igwe, C., A. (2016). Worst Forms of Child Labour in Nigeria: An Appraisal of International and Local Legal Regimes. Beijing Law Review, 7(1), 69-82. doi: 10.4236/blr.2016.71008.

- Odumosu, O. F., Odekunle, S. O., Bolarinwa, M. K., & Taiwo, O. (2013). Manifestations of the Almajirai in Nigeria: Causes and consequences (Doctoral dissertation, NIGERIAN INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RESEARCH (NISER)).

- Okeahialam, T., C. (1984). Child Abuse in Nigeria. Child Abuse & Neglect: The International Journal, 8(1), 69–73. http://dx.doi.org/10. 1016/0145-2134(84)90051-6

- Onuoha, F. C. (2012). Boko Haram: Nigeria’s Extremist Islamic Sect. Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, 29(2), 1-6

- Ottisova, L., Smith, P., Shetty, H., Stahl, D., Downs, J., & Oram, S. (2018). Psychological consequences of child trafficking: A historical cohort study of trafficked children in contact with secondary mental health services. PLoS One, 13(3), e0192321.

- Pereznieto, P., Montes, A., Routier, S., & Langston, L. (2014). The costs and economic impact of violence against children. Richmond, VA: Child Fund.

- Piot, C. (2011). The “right” to be trafficked. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 18(1), 199+.https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A268604327/AONE?u=gale15691&sid=bookmark- AONE&xid=bdddb279

- Raimi, L. (2012). Faith-based advocacy as a tool for mitigating human trafficking in Nigeria, Humanomics, 28(4), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/08288661211277515

- Rodríguez-López, S. (2018). (De) Constructing stereotypes: Media representations, social perceptions, and legal responses to human trafficking. Journal of Human Trafficking,4(1), 61-72. doi: 10.1080/23322705.2018.1423447

- Simkhada, P., Van Teijlingen, E., Sharma, A., Bissell, P., Poobalan, A., & Wasti, P. S. (2018). Health consequences of sex trafficking: A Systematic Review. Journal of Manmohan Memorial Institute of Health Sciences, 4(1), 130-150. https://doi.org/10.3126/jmmihs.v4i1.21150

- Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA). (2000). Pub. L. No. 106-386, 114 Stat. 1473

- Trafficking in Persons Report. (2022). Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, Department of State. Retrieved on April 16, 2023, from https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/nigeria/

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, November 20, 1989, https://www.ohchr.org/en